Collections

In this page

The city of Florence is home to numerous Egyptological collections, among the oldest and most important on a national and international level. The University of Florence's Egyptology courses include guided tours and workshop activities in museums, integrating lectures with the direct study of materials.

Egyptian Museum Florence

The National Archaeological Museum in Florence, one of the oldest in Italy, houses, next to the famous collections of Etruscan and classical antiquities, also the section called the ‘Egyptian Museum’, considered the second largest in Italy, in terms of size and relevance of exhibits, after the Egyptian Museum in Turin.

Established in 1855 in a palace in Via Faenza, the Museum, which included some antiquities already present in the 18th century in the Medici collections, was largely increased thanks to the Grand Duke of Tuscany Leopold II of Lorraine. ‘French-Tuscan expedition' led by Jean-François Champollion, the decipherer of hieroglyphics, and the Pisan Ippolito Rosellini, his friend and disciple, who was to become the father of Italian Egyptology.

The numerous objects collected during the expedition, either by excavations or by purchases from local merchants, were equally divided between Paris and Florence, forming the nucleus of the Egyptian collections of the Florentine Museum and the Louvre.

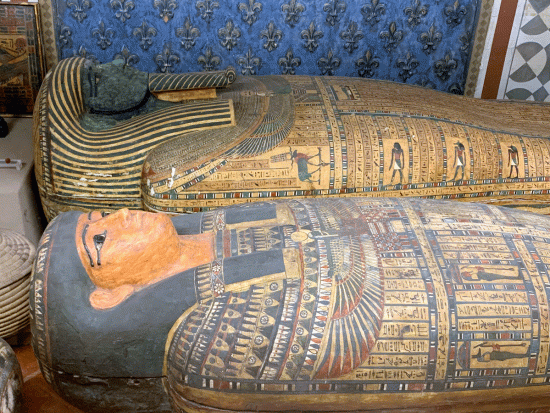

Adjacent since 1883 to the new Archaeological Museum in its present location, the Egyptian Museum underwent a vast reorganisation and a remarkable increase under the direction of E. Schiaparelli (1880-1893), thanks to his excavations and purchases made in Egypt before moving to Turin. The Museum has a didactic and chronological focus; among its most notable exhibits are the extensive collection of private stelae, a stele of Sesostri I from Nubia, the chariot dating back to the 18th dynasty, two reliefs from the tomb of Sethi I, several specimens of the Book of the Dead and of ostraca with literary compositions, the set from the intact tomb of Tjesraperet, the nurse of the daughter of Pharaoh Taharqa of the 25th dynasty, the Ptolemaic set of Takerheb, and one of the famous portraits from Fayyum.

Also noteworthy are the lot of sarcophagi from Bab el-Gusus (an exceptional find of more than 250 sarcophagi from the 21st dynasty, belonging to the Theban Amon clergy, donated by the Egyptian government to the most important Egyptological museums), and the donations by the ‘G. Vitelli’ Papyrological Institute of the Late and Ptolemaic sarcophagi from El-Hibeh (excavations 1933-1935) and the finds from Antinoe (excavations 1934-1939); among the latter, a collection of Coptic textiles that is among the richest and most important in the world.

Franciscan Ethnographic Missionary Museum in Fiesole

The convent of the Franciscan friars in Fiesole houses a small but interesting museum formed in the early 20th century with collections from the Franciscan missions in the Far East and Egypt. Its Egyptian section was set up by Father Sebastiano Bastiani in 1923, thanks to acquisitions from the Franciscan Mission in Luxor, and to the friendly relations Ernesto Schiaparelli, then Director of the Egyptian Museum in Turin, had with the friars. The antiquities range from prehistoric to Islamic times, with a prevalence of the Late Period, amounting to a total of about 240 objects, mainly ceramics, amulets, statuettes-ushabti, small bronzes, and elements of grave goods. Many of them are Schiaparelli's donations from his excavations in the Theban area, in Gebelein, Aswan and Asyut. Highlights include a mummy and a sarcophagus (not pertaining to it) from the 22nd dynasty, wooden and cartonnage sarcophagus masks, and aushabti statuette of Queen Nefertari, the great royal bride of Ramesses II.

Egyptian Papyrological Collection of the ‘G. Vitelli’ Papyrological Institute

The Institute's papyrus collection includes thousands of texts in Greek, Latin, Egyptian (Hieroglyphic, Hieratic, Demotic, Old-Coptic, Coptic) and Arabic; there is also a rare specimen in Syriac. The material, some of which is still unpublished, comes mainly from excavations carried out by the Institute in various locations in Egypt, and from purchases made on the antiquities market until the 1970s. The Greek papyri are published in the Institute's series ‘Papyri of the Italian Society (PSI)’; some of the most important published pieces are preserved in the Biblioteca Medicea Laurenziana.

The Egyptian sections of the collection (PSI inv. I, comprising papyri in hieratic and hieroglyphic, PSI inv. D, for those in demotic) consist, almost in their entirety, of papyri found at Tebtynis, in the Fayyum, during the campaigns conducted by the Institute and by C. Anti's Italian Archaeological Mission in the years 1928-1934. The majority of them come from the so-called ‘deposit’ of the library of the great temple of the god Sobek at Tebtynis, an extraordinary discovery on 10 March 1931 of two cellars filled with papyrus material, in Egyptian and Greek, from the Roman period, dated between the 1st and the end of the 2nd century AD. These are the remains of the only large institutional library that has come down to us from Egypt, and thus provide a detailed insight into the textual heritage of a Greco-Roman temple. The extremely fragmentary manuscripts, originally about 400 in number, contain cultic works, texts on temple management and the training of priests, scientific manuals in Demotic and Greek (divination, astronomy and astrology, medicine), narrative and sapiential texts. The ‘jewel’ consists of the only roll found intact, PSI inv. I 71: a hieratic copy of the ‘Book of Fayyum’, a priestly encyclopaedia illustrating a ‘mythological map’ of the oasis, listing its sacred places and their religious peculiarities, theological and cosmogonic treatises, and hymns to the crocodile god Sobek, the region's tutelary deity.

Numerose collezioni in tutto il mondo possiedono papiri da Tebtynis, ma quelli dell’Istituto sono gli unici a provenire da uno scavo controllato, e non da acquisto, e con la sicura derivazione dal “deposito” della biblioteca. L’Istituto collabora stabilmente con le altre istituzioni che conservano materiale da Tebtynis, nel comune impegno per la ricostruzione dei testi, spesso del tutto inediti, e per una comprensione globale del loro contesto archeologico e storico-culturale.

Many papyri from excavations are still in need of restoration, inventorying and study, and there are also numerous archive documents that help to clarify the history of the excavations and the papyrological and Egyptological disciplines: work that is carried out by the entire staff of the Institute, and which is constantly a harbinger of new developments.

The archaeological collection of the ‘G. Vitelli’ Papyrological Institute

The collection brings together artefacts that came to Florence from excavations conducted by the Institute in Egypt between 1964 and 1968, granted in partage by the Egyptian authorities. This material was kept for over thirty years in a storeroom of the Archaeological Museum of Florence, until space and resources were made available to the Institute for the cataloguing and restoration of all the objects, and finally for the setting up of an exhibition itinerary.

The permanent exhibition is divided into two sections. The first is dedicated to the campaign conducted by S. Bosticco in 1964/1965 at Arsinoe, the capital of the Fayyum: from here come finds from the Ptolemaic and Roman periods (3rd BC-2nd AD), such as kitchen and tableware ceramics, ointment jars, oil lamps, amphora handles with stamps, amphorae for wine and cereals, and a rich series of clay statuettes of deities. The reconstruction of the sector excavated by the Italian mission (the last before the final disappearance of Arsinoe under the modern city of Medinet el-Fayyum), and the recontextualisation of the finds are currently the subject of a multidisciplinary project within the PRIN ‘Greek and Latin Literary Papyri from Graeco-Roman and Late Antique Fayum (4th BC - 7th AD): Texts, Contexts, Readers’.

The second section focuses on Antinoupolis, briefly known as Antinoe, a Middle Egyptian city founded by Emperor Hadrian in 130 A.D. in honour of his favourite Antinous, who drowned in the Nile near that location. Excavations in 1965, 1966 and 1968 in the Northern Necropolis have yielded a wide variety of objects dating from the Byzantine and early Arab period: oil lamps, bowls, plates and trays in sealed earthenware, kitchen and tableware ceramics (achromatic and painted), wine amphorae and amphora stoppers, and artefacts in wood, metal, glass and leather. Connected to the cult of St. Collutus, a doctor martyred at Antinoupolis, are clay figurines and bronze plaques of a votive character. From the burials of the necropolis come burial cloths, clothing and accessories, such as footwear. The city of Antinoupolis was particularly renowned for the production and trade of polychrome textiles, which testify to a high level of specialisation. The collection also contains a large lot of Coptic textiles from the Northern Necropolis, restored by the Opificio delle Pietre Dure.

The Institute's excavations in Antinoupolis are still active today.

Stibbert Museum

The house-museum of the famous Anglo-Florentine collector Frederick Stibbert also contains some Egyptian antiquities, some of which are on display. In addition to the Egyptian-style temple in the park, built by Stibbert between 1862 and 1864 at the height of European ‘Egyptomania’, the museum contains a series of bronzes, amulets and ushabti, intended to serve as ‘furniture’ for the temple, some mummified human remains, and two richly decorated sarcophagi and a sarcophagus lid dating from the Third Intermediate Period to the 26th dynasty, related to the clergy of the god Montu at Thebes. They are complemented by furniture, caskets and paintings in neo-Egyptian style.

Last update

10.10.2024